Remnants of Slavery Embedded in the U.S. Prison System

With over 1.8 million people imprisoned, the U.S. has more of our citizens incarcerated than any other nation. This system is shaped by decades of legislation and cultural shifts and intersects with issues of labor, race, and economics.

When people think of slavery in America, their minds often go to the history books with descriptions of plantations, forced labor, and the Civil War. But while the formal institution of slavery was abolished with the 13th Amendment in 1865, there was an exception written into the very law that set people free: "Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States."

The United States prison system is often described as a cornerstone of justice, a place where individuals pay their debt to society. Yet beneath this ideal lies a complex web of policies, profits, and historical echoes that raise pressing questions about fairness, equity, and the legacy of exploitation. The exception embedded within the 13th amendment is at the heart of a modern issue that doesn’t always get the attention it deserves. The prison system in the U.S. today, not only punishes crime, but also functions as a labor system where inmates work for little to no pay. A system that often benefits private companies and state economies while leaving those who serve time with few real opportunities upon release.

To be clear, this isn’t a debate about whether people who commit crimes should face consequences. It’s about whether our system of punishment actually serves justice, or whether it’s set up in a way that disproportionately punishes certain groups, exploits labor, and ultimately makes it harder for people to escape the cycle of incarceration.

With over 1.8 million people imprisoned, the U.S. has more of our citizens incarcerated than any other nation. This system is shaped by decades of legislation and cultural shifts and intersects with issues of labor, race, and economics in ways that mirror past injustices while shaping present realities.

The Scope of Incarceration in America

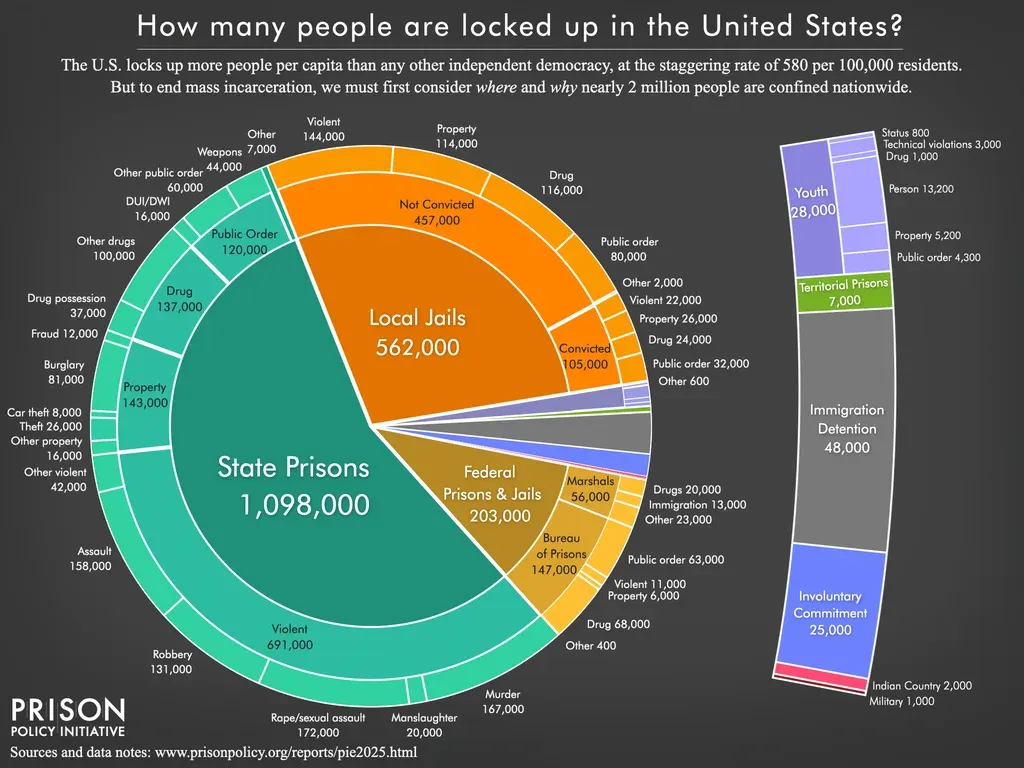

The U.S. has the fifth highest incarceration rate in the world. According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, roughly 1.2 million people are currently in state and federal prisons, with an additional 600,000 in local jails. Since the 1970s, the U.S. prison population has surged by 500%, driven by policies like the "War on Drugs" and mandatory minimum sentencing. This number has fluctuated slightly in recent years, but the U.S. still imprisons a higher percentage of its population than most other countries, including China and Russia. Today, nearly 1 in 100 adults are incarcerated.

Why? Part of the answer lies in sentencing. The length of prison sentences varies widely, not just by crime but also by who is convicted. While violent crimes account for about 40% of prison sentences, drug offenses, often nonviolent, make up 15-20%, a stark contrast to the 1980s when this figure was closer to 6%. Many of those convicted of drug offences are serving decades for crimes that, in some states, would now be legal.

Then there's recidivism (the likelihood of reoffending). Studies show that roughly 44% of released prisoners return within their first year. The number jumps to 66% within three years, and within five years, it’s over 75%. A system designed to rehabilitate should, in theory, reduce these numbers, yet they remain stubbornly high and underscore the system’s challenges.

"Mass incarceration is a system that locks people not only in physical cages but in cycles of poverty and disenfranchisement," says scholar Michelle Alexander, author of The New Jim Crow. This cycle begins with sentencing disparities that critics argue reflect systemic biases more than objective justice.

Sentencing Disparities: Who Gets What and Why

The way sentences are handed down is far from consistent. Two people convicted of similar crimes can receive drastically different punishments based on factors like race, income level, or even the judge assigned to their case. Consider two cases:

- Brock Turner, a White Stanford student convicted of sexual assault in 2016, received six months in jail (serving three) for a crime carrying a maximum 14-year sentence. The judge cited Turner’s "youth" and "lack of criminal history."

- Crystal Mason, a Black Texas woman, was sentenced to five years in prison in 2018 for casting a provisional ballot while on parole, despite not knowing she was ineligible.

White-collar crimes, such as fraud, embezzlement, or insider trading, often result in shorter sentences than drug-related offenses. A person convicted of financial crimes that defraud thousands may get a few years in federal prison (sometimes in minimum-security facilities with relatively comfortable conditions), while someone caught with a small amount of an illegal substance could face decades behind bars.

Race also plays a significant role. According to the Sentencing Project, Black Americans are incarcerated at five times the rate of White Americans, despite similar rates of offending in many crime categories. A 2023 U.S. Sentencing Commission report found that Black men receive sentences 19% longer than White men for similar crimes.

Even among victims, disparities exist. Crimes against White victims are more likely to result in longer sentences than those against Black or Latino victims. These inconsistencies raise serious concerns about whether our justice system delivers punishment fairly, or if it enforces a social hierarchy under the guise of law and order.

Pay-to-Stay: The Costs of Your Incarceration

Most people assume that once someone is in prison, taxpayers foot the bill. While this is largely true (states spend an average of $31,000 per inmate per year), prisoners themselves are often forced to cover their incarceration costs through pay-to-stay policies.

In 40 states, inmates are charged pay-to-stay fees, daily rates for their incarceration, sometimes exceeding $50-60/day. These costs, often levied retroactively, burden families already struggling with court fines and lost income.

Upon release, former inmates can be saddled with thousands of dollars in debt, making reintegration into society even more difficult. In Michigan, for example, the state garnishes tax refunds or wages to collect these debts. "I left prison owing $12,000," says Maria, a formerly incarcerated mother in California. "How was I supposed to find housing or a job with that hanging over me?"

Public vs. Private Prisons: Crime Does Pay

Though taxpayers fund the $80 billion annual cost of public prisons, not all prisons are run by the government. Private prisons are used in 27 states, housing about 8% of the total prison population and 15% of federal inmates, but their influence is outsized.

These companies are paid per inmate, and contracts often include "occupancy guarantees," which require states to keep prisons 90% full, incentivizing incarceration. The data is clear, prison is profitable, with the largest private prison operators, CoreCivic and GEO Group, reporting $4 billion in combined revenue in 2022.

Supporters argue that private prisons save states money and improve efficiency. States like Arizona and Florida contract them to reduce overcrowding, yet audits show savings are minimal, often under 5%. Reports have shown that privately run facilities often cut costs by reducing staff, medical care, and rehabilitation programs, leading to higher rates of violence and worse conditions overall.

A 2021 Department of Justice study found private prisons had 28% more safety violations than public ones.

Public prisons, meanwhile, face their own crises: understaffing, aging infrastructure, and overcrowding. Mississippi’s Parchman Farm, a former plantation-turned-prison, gained notoriety in 2020 for violent conditions and reports of inmates drinking from toilets.

States like California, Illinois, and New York have moved away from private prisons, while others, especially in the South, still rely on them heavily. The debate over their use boils down to one question: Should incarceration be a for-profit business?

From Slavery to Incarceration: How the Need for Cheap Labor Shaped the Prison System

When slavery was abolished in 1865, the American economy, especially in the South, faced a crisis. For centuries, plantation owners and businesses had relied on the forced labor of enslaved people to sustain industries like cotton, tobacco, and sugar. Without free labor, profits were at risk.

The 13th Amendment technically ended slavery, but its exception for convicted criminals provided a legal loophole. Almost immediately, Southern states began passing Black Codes, laws designed to criminalize formerly enslaved people for minor infractions like loitering, vagrancy, or not having proof of employment. These laws disproportionately targeted Black Americans, who were then arrested and sentenced to hard labor.

This system, known as convict leasing, allowed states to rent out prisoners to private businesses, plantations, and railroads. Former slave owners now had access to a new form of forced labor, except now, the state provided the workers and profited from their exploitation.

Convict leasing was brutal. In many cases, conditions for leased prisoners were worse than slavery, since businesses didn’t "own" them, there was little incentive to provide food, shelter, or medical care. Prisoners were often worked to death, with no accountability for their treatment.

This system continued into the early 20th century, with Southern states heavily dependent on prison labor for their economies. While convict leasing was officially abolished by the 1920s due to public outcry over its abuses, the idea that prisons could be used as a source of cheap labor never disappeared.

Prison Labor Today: A Continuation of the Past

Fast-forward to today, and the use of incarcerated labor has evolved but still follows the same logic: prisoners provide an easy, low-cost workforce for government projects, private businesses, and state-run industries. Industries that rely on prison labor include agriculture, textiles, technology, and even military equipment manufacturing.

Many states legally require inmates to participate in work programs, and refusal can result in solitary confinement, loss of visitation rights, or being denied parole. This system, rooted in the 13th Amendment’s exclusion of slavery "except as punishment for a crime," draws direct parallels to post-Civil War convict leasing, where freed Black Americans were re-enslaved through petty crimes.

Nearly 800,000 incarcerated people work jobs, often for pennies per hour or, in some states, nothing. Prisoners manufacture goods, sew uniforms, process meat, fight fires, and even handle customer service calls for major corporations. Corporations like Walmart, Victoria’s Secret, McDonald’s, AT&T, and Starbucks have historically relied on prison labor through programs like PIE (Prison Industries Enhancement). Inmates in these programs earn between $0.13 and $1.50/hour, far below federal minimum wage, to produce goods sold for market-rate profits.

States also profit. California and Texas use incarcerated workers to fight wildfires, with California paying them as little as $1/hour and Texas $2/day, with no post-release pathway to firefighting careers. Upon release, many are barred from becoming firefighters due to their criminal record.

Wages earned through work programs are often gutted by deductions: up to 80% for room and board, court fees, or victim restitution. Even the tiny wages they do earn are quickly diminished.

Proponents argue these programs teach skills and reduce idleness. "Work gave me purpose," says James, an inmate in Colorado who sewed masks during the pandemic. But critics note the coercion: in seven states, refusal to work can lead to solitary confinement or loss of visitation rights.

The implications of this system are significant. By continuing to use prisoners as a labor force, the U.S. has maintained an economic structure where people, disproportionately people of color, are funneled into incarceration and then exploited for their work. This cycle benefits both the government and private industry, while leaving incarcerated individuals with few resources or opportunities once released.

The transition from slavery to mass incarceration wasn’t accidental. It was an intentional shift. One that allowed forced labor to persist under a new name.

The Path is Circular: Why Do So Many Return?

If prison is meant to rehabilitate, why do most former inmates end up back behind bars? The answer often lies in what happens after release. Reentry into society is fraught with barriers:

- Many employers refuse to hire people with criminal records.

- Housing is difficult to obtain, with some landlords rejecting applicants outright.

- Probation and parole requirements can be strict and unrealistic, leading to reincarceration for minor infractions.

Many states restrict access to housing, food stamps, and voting for those with felony records. Occupational licensing laws bar ex-inmates from jobs in nursing, plumbing, or cosmetology, fields they trained in while incarcerated. So even when prisoners participate in work programs while incarcerated, those skills don’t always translate to post-prison employment. A person who worked in a prison call center can’t list that experience on a résumé, and someone who fought wildfires behind bars can’t legally apply to be a firefighter in many states.

Without livable wages or support, many turn to the same behaviors that led them to prison in the first place, not because they want to, but because survival often leaves them no other choice.

"I applied to 50 jobs after release," says Derek, a Missouri man with a nonviolent drug record. "The only offer was at a fast-food joint paying minimum wage. How was I supposed to support my kids?"

States Leading the Way on Reform

Some states have recognized the flaws in the system and are taking steps toward reform.

- Oregon and North Dakota focus on rehabilitation, offering job training, mental health services, and reentry programs that reduce recidivism.

- Maine has one of the lowest incarceration rates in the country, emphasizing alternative sentencing and restorative justice.

- New Jersey reduced its prison population by over 40% in the past two decades, largely through sentencing reforms and early release programs.

- California ended mandatory minimums for nonviolent offenses in 2022, reducing its prison population by 30% since 2006.

- Both Oregon and Colorado have banned private prisons.

- Pennsylvania expunges minor criminal records after 10 years, easing employment barriers.

The federal First Step Act (2018) expanded early release programs and rehabilitative training, though advocates argue it’s just a start. Internationally, Norway’s focus on education and humane conditions has cut recidivism to 20%, a model gaining traction in states like North Dakota.

These efforts show that alternatives to mass incarceration are possible, but they require a shift in thinking, one that prioritizes rehabilitation over punishment for the sake of punishment.

Why This Matters

Mass incarceration destabilizes families and communities. 1 in 28 American children has a parent in prison, a figure rising to 1 in 9 for Black children. Economically, incarceration costs U.S. households an estimated $7,000 annually in tax dollars, funds that could otherwise support education or healthcare.

Morally, the system’s ties to exploitative labor challenge the nation’s founding ideals. "The legacy of slavery lives on in our justice system," argues Bryan Stevenson of the Equal Justice Initiative. "Until we confront that, true equality remains out of reach."

Final Thoughts

Reforming the prison system isn’t about excusing harm but addressing root causes: poverty, lack of mental health care, and systemic bias. It requires rethinking who benefits from incarceration and who bears its costs. When a system disproportionately punishes certain groups, exploits labor, and sets people up for failure upon release, it stops being a tool for justice and becomes something else entirely: a cycle of control and exploitation.

Recognizing the prison system's role in modern-day labor exploitation doesn't mean ignoring crime or dismissing victims. It means asking whether our system is actually serving justice, or simply continuing an economic model that benefits from keeping people behind bars.

As voters, taxpayers, and community members, we shape this future. Supporting fair-chance hiring, advocating for sentencing reform, and questioning the ethics of prison labor are steps toward a system that values redemption over retribution.

In the words of former inmate and activist Shaka Senghor, "Prisons should be places of transformation, not repositories of human potential." The path forward demands both accountability and humanity. A balance that honors justice without repeating the sins of the past.