The U.S. Government: A System Built for Balance

Three distinct branches designed to keep each other in check: legislative, executive, and judicial.

Imagine playing a game where one person makes the rules, another enforces them, and a third decides whether the rules are fair. If any one player had too much power, the whole game would feel rigged. That is essentially how the U.S. government was designed: three distinct branches of power created to keep each other in check.

This structure, established in 1787, emerged from a profound distrust of concentrated power. The Founders had just fought a war to escape a monarchy, and they were not about to swap one king for another. James Madison put it clearly in Federalist No. 47: “The accumulation of all powers, legislative, executive, and judiciary, in the same hands… may justly be pronounced the very definition of tyranny.”

More than two centuries later, that system is still standing. It has bent and flexed under wars, depressions, scandals, and cultural shifts. But the question remains: does it still do what it was meant to do?

The Legislative Branch: Writing the Rules

At the heart of democracy is representation, the idea that laws should be created by people chosen by the public. That is the job of Congress.

- The House of Representatives has 435 members who serve two-year terms. Because their terms are short, they stay closely tied to public opinion.

- The Senate has 100 members who serve six-year terms, providing a more stable representation.

This setup was a compromise. Large states wanted power tied to population. Smaller states wanted equal footing. Both got something.

Congress has the authority to tax, spend, and declare war. But lawmaking is intentionally slow. A bill winds through committees, debates, votes in both chambers, and finally to the president’s desk. The idea was simple: if a proposal cannot survive scrutiny, it should not become law. Of course, that design also creates gridlock. Immigration reform, for example, has been stalled for decades. Both parties agree the system is broken, but neither is willing to give ground.

The Executive Branch: Enforcing the Rules

If Congress writes the laws, the executive branch enforces them. The president is the most visible figure, but the branch is much bigger. Cabinet secretaries, agencies, and departments, from the Pentagon to NASA, carry out policies on a day-to-day basis.

Presidential power has evolved in tandem with the country’s challenges. Franklin Roosevelt used executive orders to launch the New Deal during the Great Depression. After 9/11, George W. Bush expanded surveillance programs, raising debates about civil liberties. More recently, presidents from both parties have relied heavily on executive orders to advance their agendas when Congress is stuck, which has raised concerns about overreach.

Still, the president’s authority is not absolute. Congress holds the purse strings. The courts can strike down executive actions. Even within the executive branch, power is spread across agencies and cabinet leaders.

The Judicial Branch: Calling the Plays

Laws do not mean much without interpretation. That is where the courts come in, with the Supreme Court at the top. Justices are appointed for life. The intent is to free them from political pressure, though critics argue it also makes them less accountable.

The Court’s rulings have reshaped the nation. Brown v. Board of Education ended segregation in schools. Roe v. Wade established abortion rights, only to be overturned decades later in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization. These decisions demonstrate the Court's significant influence and how that influence evolves over time.

The confirmation process for justices has become highly partisan. The battles over Merrick Garland in 2016 and Amy Coney Barrett in 2020 demonstrated how nominations have become proxy fights for larger cultural issues.

Checks and Balances in Motion

The strength of the system is not only that powers are separated, but that they constantly collide with one another.

- Congress can override a veto or approve judicial appointments.

- The president can veto bills or nominate judges.

- The courts can strike down laws or executive actions.

These checks are not just theoretical. When Richard Nixon refused to hand over the Watergate tapes, the Supreme Court ruled against him, and he resigned under threat of impeachment. In 2013, gridlock between Congress and the White House triggered a government shutdown, resulting in the furlough of 800,000 workers. The system does not always look efficient, but conflict was part of the plan.

Federalism: Another Layer of Balance

Power is also divided between federal, state, and local governments. That is why laws differ from state to state.

- The federal government handles defense, immigration, and interstate commerce.

- States oversee education, transportation, and health care policies.

- Local governments manage schools, zoning, and community safety.

Sometimes this division sparks innovation. Massachusetts passed a statewide health care law in 2006 that became a model for the Affordable Care Act. Sometimes it sparks conflict. Federal and state leaders clashed over mandates during the COVID-19 pandemic, revealing both the strengths and limitations of decentralized power.

The People: The Final Check

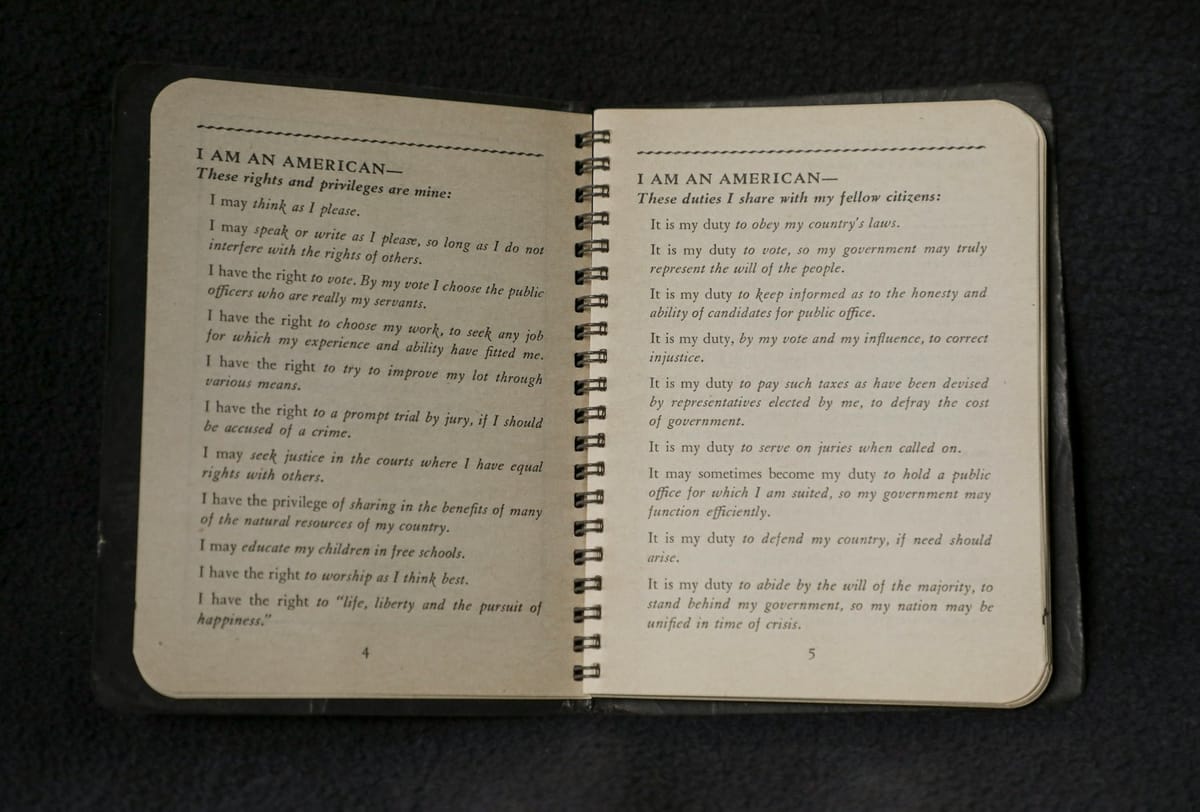

The Founders built one last safeguard outside of government: the people. “We the People” was not rhetoric. It was the point.

The system only works if citizens participate. Voting is the most direct way, but engagement goes far beyond elections. Protest, jury service, civic activism, and watchdog journalism all help prevent power from concentrating in the hands of a few. When people disengage, balance shifts. Low voter turnout and apathy let power concentrate in fewer hands. Dwight Eisenhower once said that politics should be a part-time profession for every citizen. He was right. Democracy is a living system, and it weakens if people step away from it.

Does the System Still Work?

For more than two centuries, the U.S. government has survived wars, depressions, scandals, and sweeping cultural shifts. But trust has eroded. In the 1960s, over 70 percent of Americans reported trusting the federal government. Today, that number is closer to 20 percent.

The reasons are clear. Gridlock makes progress feel impossible. Lobbying and money in politics give the impression that influence is bought. Congress often does not reflect the diversity of the country it represents. None of these challenges erases the system, but they do weaken confidence in it.

Final Thoughts

The U.S. government is not perfect. It is slow. It is messy. At times, it feels broken. But that messiness is part of the design. It keeps power from concentrating in one place.

Still, checks and balances do not run on autopilot. They rely on people showing up. Voting, staying informed, demanding transparency, and engaging in challenging conversations are not extras; they are essential. They are what keep democracy alive.

Sandra Day O’Connor once said, “We don’t accomplish anything in this country by tearing each other down. We do it by working together.” That begins with each of us choosing to listen, participate, and hold leaders accountable.

The three-branch system was never built for efficiency. It was built for fairness. Whether it stays that way depends not only on leaders, but on all of us.